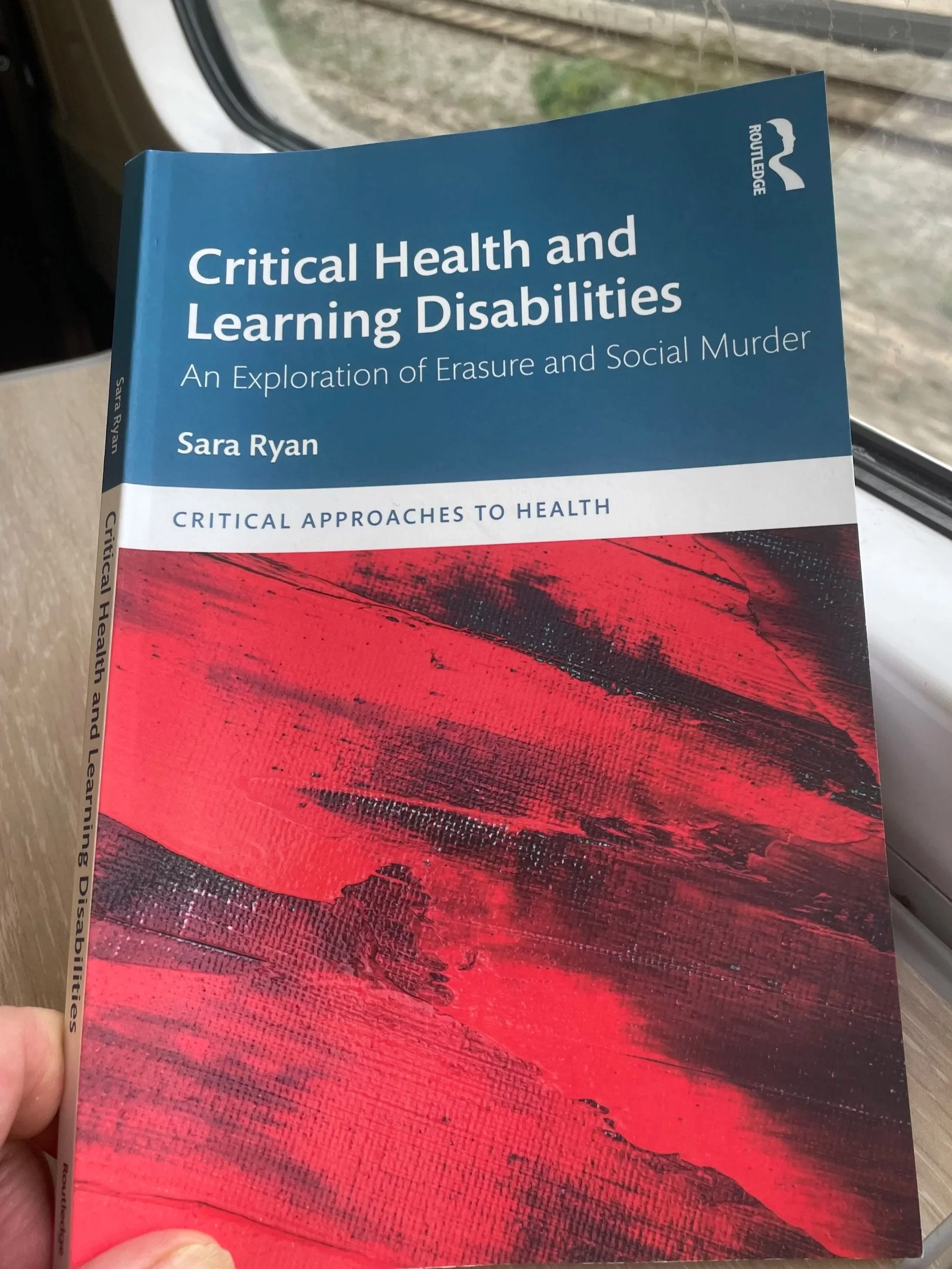

Sara Ryan’s new book, Critical Health and Learning Disabilities, came with a trigger warning. This, I gathered, presented an entirely pessimistic vision of the lives of people with learning disabilities, and would be traumatic for anyone who loves or cares for a person like my Joey. I was prepared for the worst.

It’s perhaps a sign of just how dark the reality is, but also how precise and honest the book is, that I didn’t find it nearly as harrowing as I feared. Those without lived experience might be appalled, but for the rest of us Sara simply describes a world that we recognise all too readily.

At the heart of the book is an exploration of how in four fundamental aspects of human life—healthcare; love and sex; housing and employment; food and eating—people with learning disabilities are consistently denied the same rights and dignities that are extended to (pretty much) everyone else.

People with what we loosely call learning disabilities, she shows, are the ultimate outgroup, an outgroup who the mighty scholar Chris Goodey explains, is ‘excluded even from the idea that outgroups can challenge their own marginalisation.’ They are still, as the psychiatrist Leo Kanner wrote back in 1942, placed in the ‘human waste basket’.

The result, Sara shows, is an almost universal inability to see them as individuals. Despite the fact that no-one died of a learning disability, their health outcomes are dreadful, largely as a result of the way that medical professionals fail to engage with them. This was shown most starkly in the pandemic, but is also evident in the dysfunctional roll out of annual health checks, and the continuous failure for doctors to diagnose all the other usual ‘natural shocks that flesh is heir to’. And then of course there are the dreadful long stay units where far too many people with learning disabilities are left to languish in squalor, loneliness and despair.

The average life expectancy for a man with learning disabilities today is said to be 63 and there are far too many premature and unnecessary deaths. This is vividly shown in the systematic failure to report on the reasons for such deaths accurately with the conclusion too often being a glib ‘of natural causes’ with the simple conclusion ‘nothing to be seen here’. The very lack of interest speaks volumes of the inability to perceive the victims as human beings.

Crucially, as Sara insists, ‘poor health outcomes among people with learning disabilities should be considered intolerable rather than a given. We remain all too practiced in tolerating them.’

The book then covers the way that people with learning disabilities are so often denied the chance of sexual relationships, live in deeply inappropriate places and are excluded from all the entirely human experience of eating food together. In every case, Sara shows, these problems are created by people who should, and probably do, know that a better, more human way is possible. It’s certainly what they’d expect for themselves and their families: why on earth do people with cognitive impairments deserve anything less?

Sara rightly resists the simple structural solutions which so often appear in long delayed and ineffectual reports and policy statements. The problem goes much deeper than simply a lack of training, better regulation or more money. Indeed, she shows how the very same lack of humanity and imagination exists in the impeccably liberal research community, with one academic preposterously wondering whether ‘exercise is valuable to people with learning disabilities’.

Sara’s subtitle—An Exploration of Erasure and Social Murder—sets out the book’s core intentions. In Beautiful Lives, I describe the metaphorical oubliette into which people with learning disabilities have so often been cast in the past. What Sara shows is how the old practices take new forms in the modern world but are a consequence of the same age-old inability to see people with cognitive impairments as human beings. Erasure is everywhere.

Sara takes the explosive term ‘social murder’ from Friedrich Engels, who argued in 1845 in The Condition of the Working Class in England that when ‘society knowingly places people in such a position that they inevitably meet an unnatural death’, and ‘yet permits these conditions to continue, it is guilty of social murder’. Crucially, this is a kind of murder ‘which does not seem what it is, because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one, since the offence is more one of omission than of commission. But murder it remains.’ Sara has chosen the term for good reason.

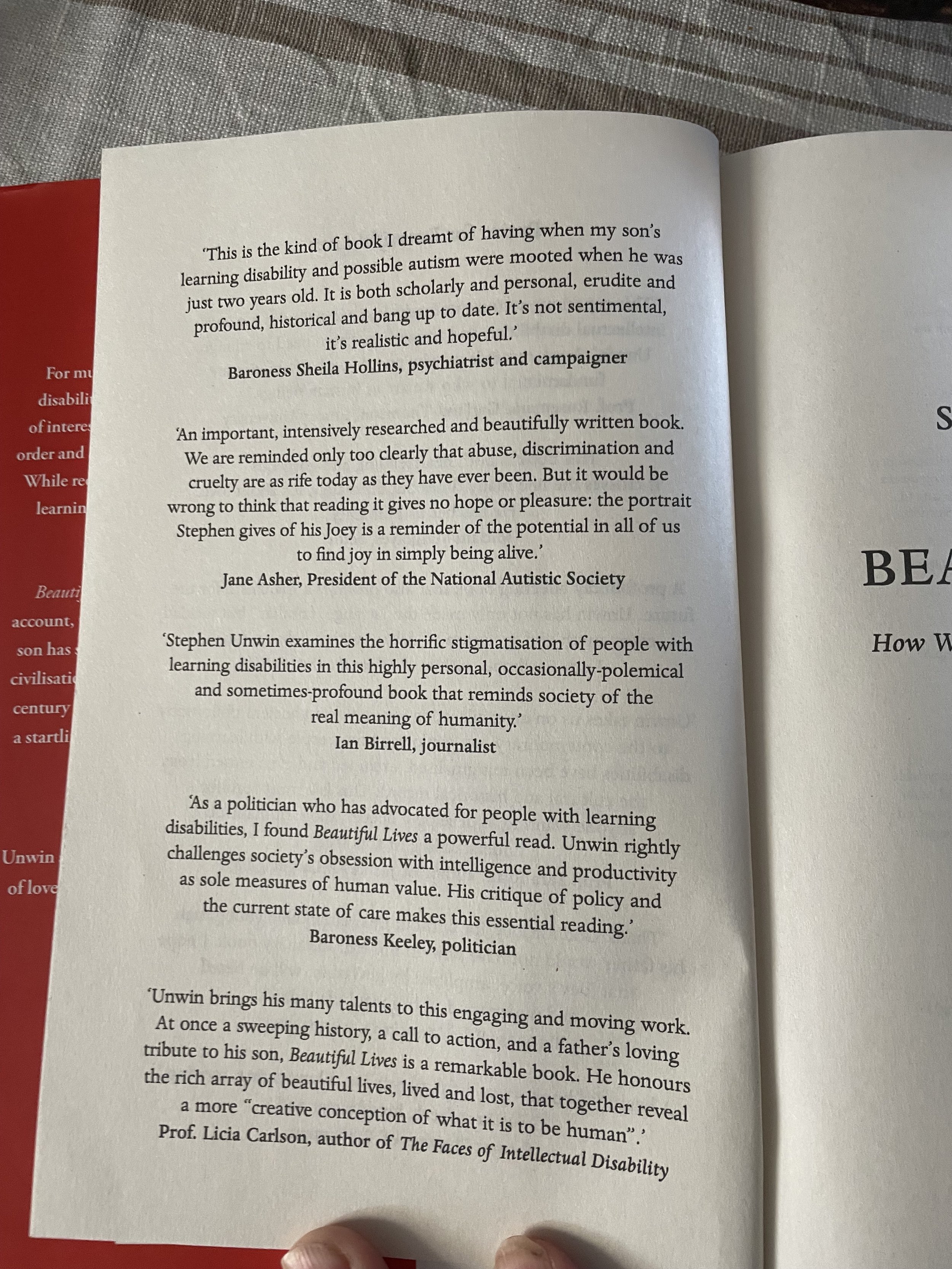

This is an essential book: impassioned but clear, scholarly but readable, challenging but true. Twelve years after the entirely avoidable death of her son Connor in an NHS run Assessment and Treatment Unit, Sara Ryan is an extraordinarily powerful voice, still challenging us all to be better, and refusing to take no for an answer.

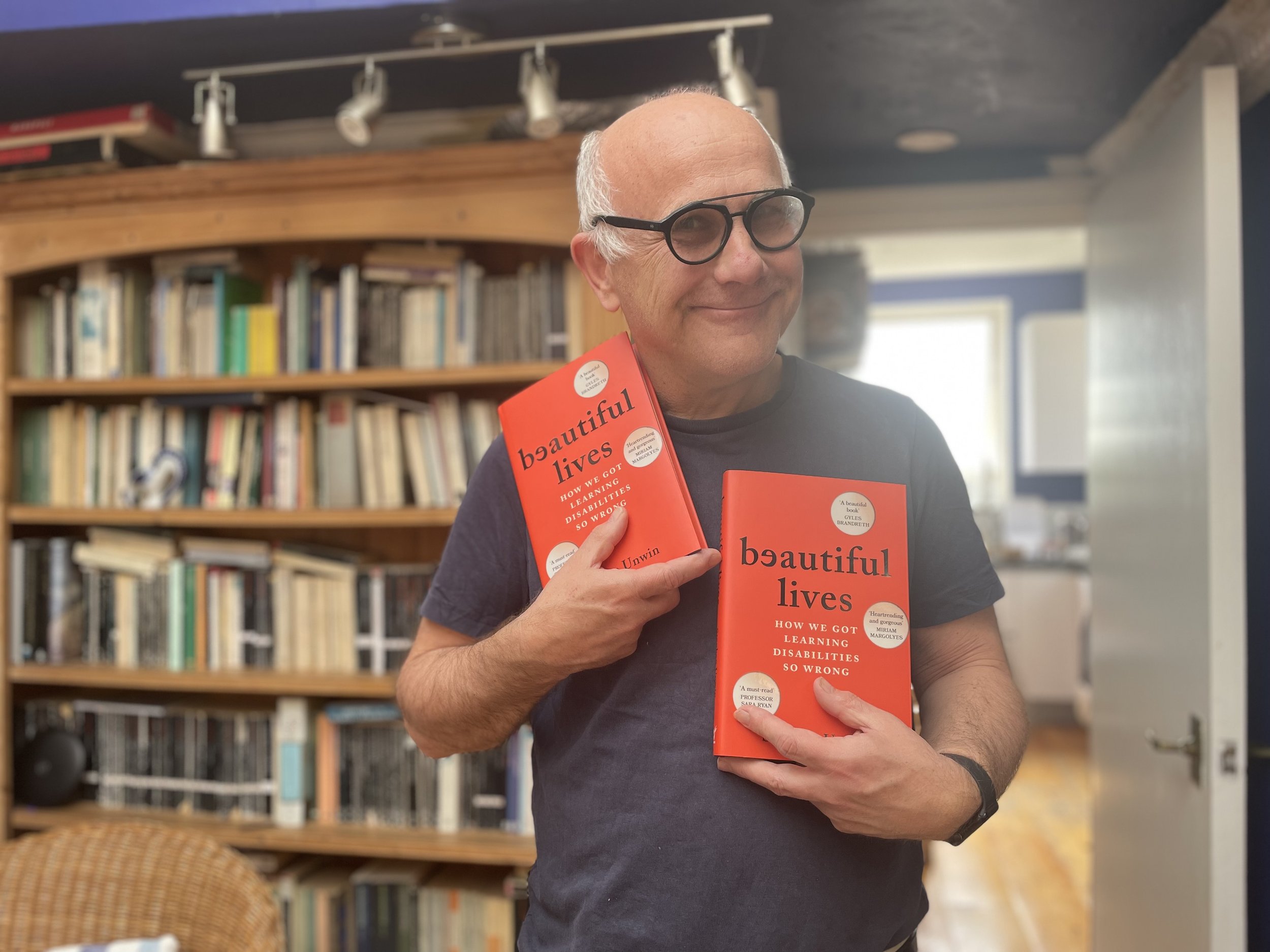

So terrible being the dad of a learning disabled young man. pic.twitter.com/innKcdKFje

— Stephen Unwin (@RoseUnwin) January 1, 2021 " target="_blank" class="sqs-svg-icon--wrapper twitter-unauth">