I was honoured to be asked by Professor Martin to give this lecture and very grateful to Michael Lewis and his wife, Janina, as well as everyone at London South Bank University, for their generosity and hospitality.

I will admit, however, to deep-rooted impostor syndrome. I’m no scholar. I have no paid academic perch, no PhD. The best I have is a degree in English literature from a chilly university in East Anglia, but I’m not sure if that counts.

What I do have, though, is extensive lived experience. My lovely second son, Joey, now 25, has no speech, intractable epilepsy and severe learning disabilities. Here are some pictures.

He has a big smile and an infectious laugh but needs help with the most basic of life skills: changing his clothes, cooking his dinner, going on a bus, brushing his teeth, toileting and the rest. He can say ‘no’, yes’ and, delightfully now, ‘cup of tea’ and, communicates with a mixture of very simple Makaton and persistence. He is much loved by many, and generates huge joy, but there is no denying the severity of his learning disabilities.

And this experience is central to what follows. For the fact is being Joey’s dad has changed my life. I’ve become a campaigner for the rights and dignities of learning-disabled people, written plays and articles about the subject, appeared on the radio and chaired KIDS, a superb national charity supporting disabled children, young people and their families.

It has also challenged many of my most deeply held assumptions about the worth of intelligence itself, and helped me rethink the values that I was brought up to cherish.

I’ve spent the last two years writing a book. The Golden Smile — still unpublished — is an attempt to show how changing attitudes have led to changed lives, both for good and ill, from the Greeks to the present day. It’s made me understand that it’s impossible to support people with learning disabilities without a clear understanding of the culture that surrounds them. The two are intimately related.

And that is the issue, and the many contradictions that it throws up, that I want to look at tonight. For I think better ways of understanding the subject will provide the basis for better lives, not just of learning-disabled people, but for all of us.

+

Let me start with a simple contradiction: the way the process of diagnosis and labelling hasn’t always helped.

It was in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that intellectual disability emerged as a distinct category, with ‘idiots’, as they were increasingly called, being seen as a specific subsection of humanity, requiring specialist education, support and care, while also prompting questions about the nature of their condition, and to what extent they could be accepted into the category of the human.

But this wasn’t always the case. As Simon Jarrett shows in his magisterial study, Those They Called Idiots, learning-disabled people in Georgian London were absorbed into the general population. And, as Chris Goodey and others, have argued persuasively, it’s difficult to discover evidence of learning-disabled people before the arrival of such taxonomy. It’s not that they didn’t exist, it’s that they weren’t widely recognised as a distinct group — except, importantly, in law, where their capacity had an impact on money and property.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, and influenced by the pseudo-science of eugenics, learning-disabled people were increasingly seen as an existential threat, what was called ‘a social menace.’

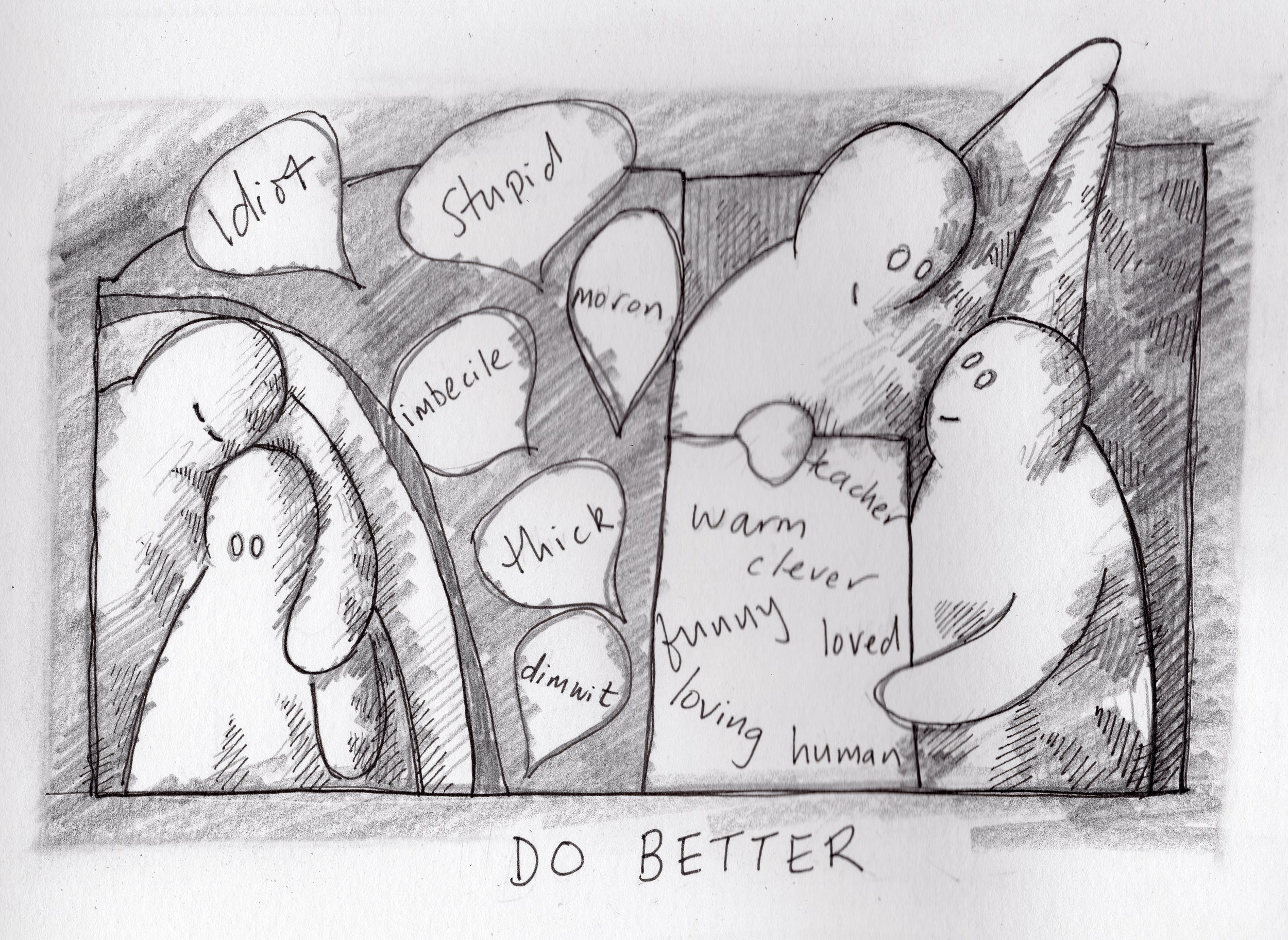

They were divided into categories, with ghastly terms like ‘imbeciles’, ‘the feeble minded’, ‘morons’, ‘mental defectives’, and the rest, all indicating varying degrees of mental impairment. These categories then dictated accommodation in asylums, institutions and colonies, with the most disabled placed as far away as possible. The melancholy fact is that Joey wouldn’t have been welcome in the high street.

And soon, responding to an entirely unscientific fear of the heritability of learning disabilities, thousands of people across America and continental Europe were forcibly sterilised, leading, ultimately, to the horrors of the Nazi persecution, which caused the deaths of as many as 250,000 disabled people.

If only this had been the end of it. But eugenic thinking was hardly discredited. Indeed, in 1943 William Beveridge slipped out of the gallery of the Commons where he was watching the debate about his famous report to reassure the ladies and gentlemen of the Eugenics Society that his plan was, quote, ‘eugenicist in intent and would prove so in effect.’

And soon new names appeared: ‘subnormality’, ‘retardation’, ‘mental handicap’, ad nauseam, with further provision dictated — and rationed — by such labels.

And, of course, the process continues.

Now, I recognise that identifying and naming the cause of the impairment can help in practical ways and I’m certainly not anti-science. But I often find myself quietly content that Joey — who is what is beautifully called a SWAN: a syndrome without a name — doesn’t have a label. What matters is ensuring that he has a good life, not what words can be used to describe his apparent defect. In other words, a label doesn’t guarantee a better life. At times, it’s done the opposite.

It’s just the first of many contradictions.

+

A second can be found in the way that artists and intellectuals — many of them self-proclaimed progressives — have responded to learning-disabled people.

And it’s pretty grim stuff, I’m afraid.

Thus, Bernard Shaw insisted that ‘the only fundamental socialism is the socialisation of the selective breeding of man’, under which ‘we should find ourselves committed to killing a great many people whom we now leave living, and to leave living a great many people whom we at present kill’. ‘Eugenic politics’, he insisted, ‘would finally land us in an extensive use of the lethal chamber’, and ‘a great many people would have to be put out of existence simply because it wastes other people’s time to look after them’.

Using the same ghastly phrase, D. H. Lawrence described ‘a lethal chamber as big as the Crystal Palace, with a military band playing softly’. He volunteered to ‘bring them all in, the sick, the halt and the maimed’ saying that he ‘would lead them gently, and they would smile me a weary thanks; and the brass band would softly bubble out the Hallelujah Chorus.’ It sounds like a suburban Treblinka.

Perhaps most shocking of all is Virginia Woolf’s diary entry for 9th January 1915, where she writes that:

‘On the towpath we met & had to pass a long line of imbeciles. The first was a very tall man, just queer enough to look at twice, but no more; the second shuffled, & looked aside; and then one realised that everyone in that long line was a miserable ineffective shuffling idiotic creature with no forehead, or no chin, & an imbecile grin, or a wild suspicious stare. It was perfectly horrible. They should certainly be killed.’

No room of their own for that lot, it seems.

The fact is that learning-disabled people have been the subject of continuous prodding by intellectuals for centuries, with classical philosophers from Plato to John Locke wondering whether they should be numbered among the human. And this line of inquiry persists to this day.

Thus, the geneticist Richard Dawkins, in response to an enquiry from a woman about what to do if she found she was carrying a foetus with Down’s, replied ‘abort it and try again. It would be immoral to bring it into the world if you have the choice’. He denied eugenicist intent, but it’s hard to understand what he meant by ‘immoral’ in such a context. He also tweeted that it’s wrong to ‘conclude that eugenics wouldn’t work in practice’, insisting that ‘it works for cows, horses, pigs, dogs & roses. Why on earth wouldn’t it work for humans?’

An even more egregious example is Peter Singer, Distinguished Professor of Bioethics at Princeton, who has argued that human beings like my Joey who fail to develop speech should be seen as less than human, insisting that ‘If we compare a severely defective human infant with a nonhuman animal . . . we will often find the nonhuman to have superior capacities, both actual and potential, for rationality, self-consciousness, communication and everything else that can plausibly be considered morally significant.’

Singer was involved in a public meeting with the remarkable philosopher Eva Feder Kittay, the mother of a woman with profound learning disabilities. Kittay showed up the shallowness of his arguments, above all that he knew virtually nothing about learning-disabled people themselves. When he tried to reassure Kittay that he had no desire to hurt her feelings, she went to the heart of the matter:

‘That’s not what it is about. For me, it’s not what I am experiencing, it’s what your writings might mean for public policy. That's what concerns me. And that’s not just about my daughter.’

Her warning about dissociating philosophy from the everyday realities of care is essential, especially, perhaps, in the groves of academe.

Such contradictions can be seen in less exalted places too: when England lost the European football final, Twitter was ablaze with progressives condemning the ‘racist morons’ who were blaming the black players who’d failed to score the penalties. Racism is bad, it seems, but learning-disabled people are fair game.

Progressive should recognise the experience of learning-disabled people and acknowledge their own historic prejudices in this area.

+

A different kind of contradiction can be found in the 1960s theory of ‘normalization’. This posited the unremarkable if essential idea that learning-disabled people should be able to live normal, ordinary lives, and has had a huge impact.

Normalization wasn’t quite as new as its proponents claimed. What was novel was its scale and ambition: this wasn’t just a better way of looking at vulnerable people, it was a comprehensive approach to lives, services and culture.

Normalization, however, begs various questions. The first is that, despite protestations to the contrary, it was, especially in Europe, seen in the context of hospitals, which could offer, I quote, ‘an intensive training environment which, whilst not normal in itself, will nevertheless help to normalise people’.

Then, many of the definitions of ‘normality’ reflected the values of the time. Thus, one (male) champion declared that ‘residents are encouraged to undertake the roles they would have in a normal family, the women doing the domestic chores and assisting in the day-to-day care of the children and the men going out to work’. ‘Normality’ is as much of a social construct as the ‘abnormality’ it was trying to displace, it seems.

Third, under normalization, learning-disabled people were expected to lead lives like the rest of us, with little interrogation of the ways that ‘normal society’ needs to change, not just in terms of attitude and understanding, but legislation and public expenditure.

Perhaps normalization’s most contentious assumption was about what learning-disabled people actually want. Central to the identity of many is a defiant unconventionality, with a rejection of many of the norms of mainstream society: after all, why should they be like everyone else?

For the fact is, learning-disabled people come in all shapes and sizes, and any generalisation is counterproductive. (Like all of us, one might add.)

In other words, the blanket notion of ‘normality’ should be resisted if we’re to engage properly with the needs and lives of this very loosely defined and heterogeneous group.

Or maybe we just need to think more carefully about what we mean by ‘normal’.

+

‘Normalization’ was in many ways a reaction against the dreadful conditions discovered in institutions for learning-disabled people. The accounts are stomach churning: in America, Willowbrook, Letchworth Village and the Fairfield Hospital in Oregon; In Britain, South Ockenden, Normansfield or the Ely Hospital in Cardiff, to name just a few.

Let one stand for many. Thus, in 1972, the journalist Geraldo Rivera made a television documentary about Letchworth in upstate New York. He wrote of the young girls he found in one of the buildings. ‘Many of them had physical deformities; most were literally smeared with faeces’, and concluded with words that should shame us all:

‘But they were, after all, just little girls. And those little girls — just like your sister or daughter — wanted to be held and loved. When we walked into the wards, they came towards us. I wanted to hold them, but it was too frightening. They were like lepers, and I was afraid they would somehow infect me.’

Rivera could have been at the liberation of Dachau, and it’s hardly surprising to read his impassioned cry: ‘We’ve got to close that goddamned place down!’

And indeed, as a result of such justified outrage most of these places were closed down and the people who lived there were moved.

But it’s here that another contradiction emerges. Because all too often residents were torn from the places they’d lived in for their entire lives and abandoned with not enough help or support in the so-called ‘community’. There are dreadful stories of people being moved into flats with just one black plastic bag containing all their worldly possessions. In other words, it’s not good enough to close bad institutions down if you don’t have suitable accommodation for the people to move into.

What’s more, the move from the institutions didn’t stop the violence and cruelty chronicled so harrowingly in Katherine Quarmby’s Scapegoat. Indeed, learning-disabled people living lonely lives in the community seem particularly prone to such attacks.

It’s not even as if the curse of bad institutions was lifted. Although many of the large ones were closed, smaller ones survived, some even thrived, and we now find ourselves in the grotesque situation of private care companies making vast profits running homes and communities which are frankly not fit for purpose, with dreadful stories of neglect, cruelty and abuse. You know the names: Winterbourne View, Whorlton Hall, Muckamore Abbey, ad infinitum it seems.

And then, of course, there are the ATUs and other deeply unsuitable hospital settings where some of the worst violations of human rights have taken place, often defended as a response to so-called ‘challenging behaviour’.

In other words, it’s not good enough to declare ‘institutions bad, community good’. Instead, we should understand what it is that individuals require, and create accommodation and support which is responsive to their needs.

I know this from experience. When Joey’s epilepsy became dangerous, it was obvious he couldn’t live at home anymore: after all, epilepsy at night unsupervised can be fatal. His mum and I had to shock the local authority into taking his needs seriously and place him in an epilepsy specialist centre, to which he is still attached. There are not many of them. I dread to think what would have happened without it.

We should attend to such contradictions.

+

Normalization was followed by a more radical idea: that learning-disabled people should shape their own lives and plot their own future. With its mantra of ‘nothing about us, without us’, self-advocacy argues that the best way to secure flourishing lives is to let learning-disabled people speak for themselves and listen to what they have to say.

It’s hard to establish a definitive history of self-advocacy (and needs a self-advocate to write it) but the spark was struck when a conference included learning-disabled delegates for the first time. When, the next year, a group was discussing what to call the emerging movement, someone called out: ‘I’m tired of being called retarded — we’re people first’. And the inaugural People First conference soon followed. It’s now a worldwide movement.

Self-advocacy means different things in different contexts, but every self-advocate believes that a learning-disabled person is a person first, not a condition who should be responsible for all decisions about their lives.

They want to live and learn alongside other non-disabled people of their own age, be allowed to make mistakes, and not be constantly constrained or labelled: ‘Label jars, not people’, as the motto runs.

The fact is, however, that self-advocacy — probably the most significant advance in this whole dark history — has its own contradictions, especially when it comes to people with severe learning disabilities, where self-advocacy by its very nature privileges the most articulate.

Because, of course, some learning-disabled people don’t have a physical voice at all. Some can communicate their wishes with assistive technology and others have elective mutism. But for people like my Joey, who has only just mastered ‘cup of tea’ at the age of 25, insisting that he should speak up for himself is unrealistic and counterproductive.

I have seen these contradictions in action when well-meaning social workers have asked for Joey’s views on his future. They provide forms which ask the person to complete a sentence beginning with an ‘I’: ‘I want to do this’, ‘I want to live like that’, and so on. But I’ve sometimes had to stifle my laughter, not at the nobility of the aspiration but the gap between it and the reality. Because when I write ‘I want to live with my friends’, I’m actually writing on Joey’s behalf. I’m speaking over him — at best a form of ventriloquism — and the opposite of what self-advocacy should be all about.

And here, of course, we run into another contradiction: if you ask Joey what he wants to eat he will inevitably sign ‘spaghetti’ and ‘sausages’. But we know that he, like all of us, needs five fruit or veg a day. If we insist on it for ourselves, we should insist on it for people with learning disabilities too. Anything else is, frankly, neglect.

In some ways these contradictions simply reflect the range of impairments covered by the blanket term ‘learning disability’. But there is, I believe, a way through and that is to rethink self-advocacy as a continuum: that is, we’re all dependent on others to help with things that we find difficult, and no-one is a self-advocate in everything they do.

And so I think we should seek a less binary definition of self-advocacy. For Joey’s presence at a meeting about his future is a speech act in itself, and should be understood as such. He may not be speaking in the ordinary sense of the word, but his beating heart and living breath make him much more than just a name on a sheet of paper.

Some self-advocates object to the voice of parents like me, especially when their offspring are over 18. But while some parents present obstacles, whether from a lack of imagination, an excess of negativity or unresolved feelings of grief, they shouldn’t be too heavily criticised if they don’t always get the balance right. They’re not necessarily infantilising their loved ones if they worry about their welfare. For it is love, overwhelming love, that drives them and there are far too many stories of family members being excluded from critical issues resulting in catastrophic consequences to calmly hand over all responsibility to professionals, however decent and committed they may be.

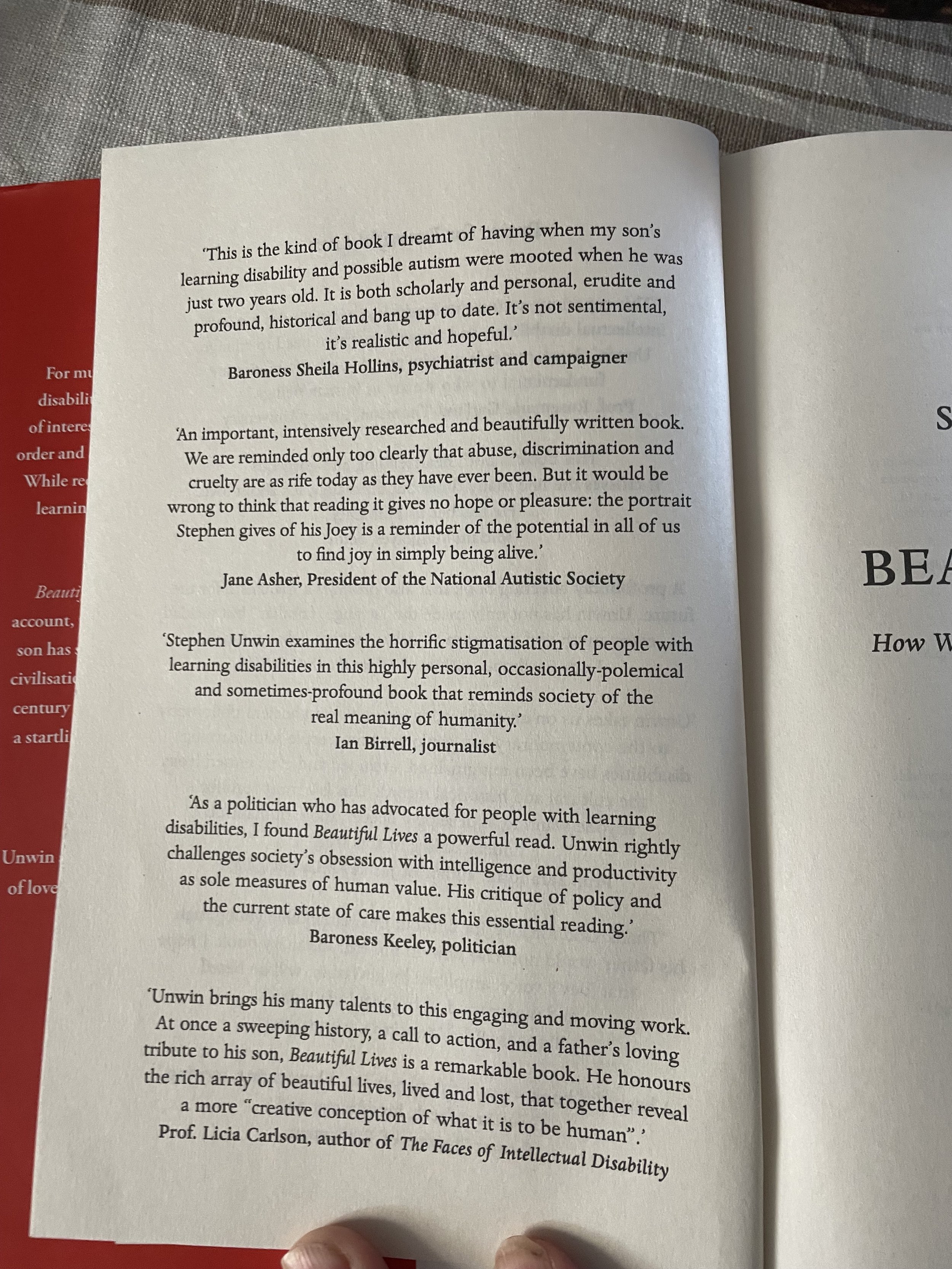

What’s more, parents have often led the way, from Judy Fryd founding Mencap in the 1940s, to Sara Ryan’s inspirational campaign for justice for her beautiful son, Connor, more recently. And there are so many others.

In conclusion, then, while the movement to ensure that learning-disabled people can enjoy full human rights is immeasurably strengthened by the voices of the learning disabled themselves, we should recognise its inevitable limits when it comes to articulating the wishes of people with the most profound disabilities.

Anything else is, quite frankly, ableist.

+

Further contradictions can be found in the ‘social model’ of disability.

This insists that instead of talking about deficit, we should accommodate difference. Above all, that we should stop regarding disability as pathological and understand it as something that society needs to engage with and adapt to accordingly. In other words, that people are disabled by the world, not by their impairment.

The social model has had a massive impact. I’ve certainly found it useful when I’ve challenged the authorities about why Joey is excluded from opportunities that his non-disabled brother and sister take for granted. As I see it, the social model reminds us that a well-organised society upholds the individual’s rights as a matter of course,

For all its strengths, however, it begs some questions.

First, it fails to acknowledge the full extent of some disabilities, including the medical issues that are sometime comorbidities: Joey’s epilepsy is just one example. And, of course, learning-disabled people face perfectly ordinary medical issues of their own, which are too often overlooked

The problem is that even well-meaning health professionals sometimes let them down. This came clear in the Covid-19 crisis when learning-disabled people initially appeared lower down the triage order and weren’t prioritised for vaccination among vulnerable groups. And, appallingly, they suffered much higher death rates than any other group.

Second, the social model is more useful with physical than learning disabilities, especially severe ones. It’s one thing to insist on ramps to make buses physically accessible, but quite another to insist that bus drivers learn Makaton. Accommodating different kinds of minds isn’t necessarily straightforward.

The social model has led to a further debate about whether we should regard learning disabilities as an impairment at all, with some insisting that people without evident physical disabilities aren’t, in fact, disabled. Others say that we should be talking about ‘learning differences’, not ‘learning disabilities.’

I’m afraid I have a problem with this. Which is not to say that someone like Joey is only disabled: after all, he has a definite personality, settled preferences and a highly developed sense of humour. But there are many things he can’t do that almost every human being his age can do, and hardly anything that he can do which others cannot. As such, he is distinctly disabled and it’s dishonest to say anything else.

One of the chief consequences of the social model is ‘inclusion’—the idea of including learning-disabled people in all aspects of everyday life: education, housing, healthcare, and so on. This is widely taken for granted as a good and some argue that there should be no specialist provision at all.

And while I recognise the nobility of these aspirations and agree that inclusion can be hugely valuable (for the non-disabled as much as the disabled), I’m not convinced that such a one-size-fits-all approach is sensible in practice. Apart from anything else, some learning-disabled people want to live, study and hang out with other learning-disabled people. Joey’s best friends all have learning disabilities of one kind or another and we should be alert to that.

Indeed, those who insist on absolute inclusion in education should also insist that severely learning-disabled people should go to the best universities. I once had a ding-dong with the Dean of a posh American university who proudly insisted that her institution was ‘fully accessible’: ‘not for people with profound learning disabilities’, I pointed out, not because I thought they should accept people like my Joey, but because I thought they should be honest.

+

For good reasons, learning-disabled people and their families are often encouraged to move away from the ‘tragedy’ model. And, certainly, there are many positives in the experience.

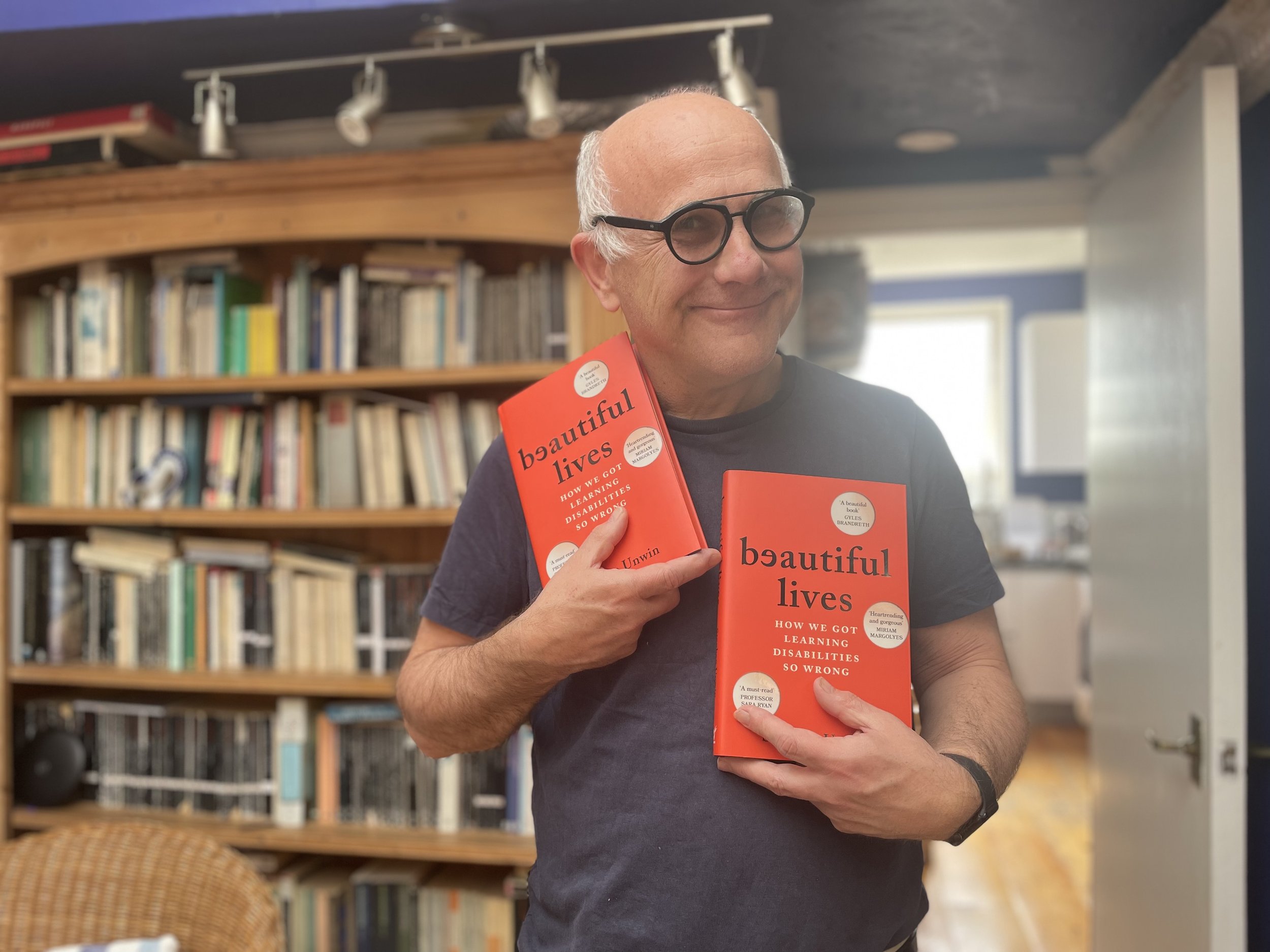

I encountered this on Twitter of all places. It was the afternoon of New Year’s Day 2021, and I was lying on the sofa with Joey, giggling at one of our jokes. I took a few selfies and tweeted one of them with the simple, ironic message: ‘So terrible being the dad of a learning-disabled young man.’ I thought nothing more of it until I returned to my phone and saw a steady stream of notifications. I was especially struck by the scores of pictures of families with a learning-disabled relative doing happy, ordinary things: climbing mountains, walking on a beach, bouncing on trampolines and posing in pyjamas, all laughing, smiling and having infectious, glorious fun.

Each carried its own message of mock gloom (‘another day of misery’; ‘awful sadness’; ‘such dreadful hell’) to which I replied with mock sympathy: ‘Oh how awful’; ‘So grim’; ‘Thoughts and prayers’, etc. For three frantic hours, I could hardly keep up, and when I woke up on Saturday it was still going strong (23,000 ‘likes’). By Monday morning I was on Radio 4 talking about what had happened and what it meant.

It was clear that Joey and I had struck a chord. Because families of learning-disabled children are so often made to feel their situation is desperate, my tweet encouraged them to demonstrate that they don’t just love their person to the moon and back, but he or she has taught them more about life, love and laughter than anyone could possibly imagine.

Something similar happened on the day children get their GCSE results: I tweeted a picture of Joey with a request to ‘remember the young people who’ve never got a qualification in their lives’ which got a huge response. The biggest, however, was on Joey’s 25th birthday, when I posted a picture with the simple message that, ‘He’s never said a word in his life, but has taught me so much more than I’ve ever taught him.’ It received almost 90,000 ‘likes’ and 2000 ‘retweets’ and was, for a moment, ‘trending’. The point is that people were—if only for a moment—opening their hearts and minds to learning-disabled people and recognising their value. It was a genuine political moment.

But while I love the positivity that my tweets have unleashed, I think we should be careful, and not just because Twitter is an echo chamber desperately prone to confirmation bias.

The first reason is because parents and siblings shouldn’t be bullied into stifling negative emotions. There are many times when Joey’s family find him infuriating and we sometimes compare the trigger points, the things that we find especially challenging. Acknowledging, exploring and forgiving ourselves for these responses is essential not just for us, but him too.

The bigger danger about such boosterism is that it creates hierarchies within learning disabilities.

As an example, Mencap has recently rolled out an awareness campaign called ‘MythBusters’. This aims to discredit the idea that learning-disabled people are incapable, and profiles a number of learning-disabled people who are achieving great things. This, it’s felt, will help the public think of learning-disabled people in a more positive way. So far, so good.

The arts often do something similar, producing uplifting stories of learning-disabled people overcoming the odds to do remarkable things, but usually without reference to the social context which is where the real battle happens.

The danger with all this is that it creates a hierarchy within learning disabilities, with the ‘MythBusters’, the exceptions, at the top and people like my Joey at the bottom. It unwittingly suggests that people only deserve support if they’re capable of achieving great things. The law of unforeseen consequences, I suppose.

The underlying problem is the very notion of the meritocracy. We all think wealth, power and opportunities shouldn’t be inherited but earned. But not only is this an illusion, it doesn’t help people who fail these tests.

As I often say, every family of a learning-disabled child or young person is different; what unites us is the endless struggle for fundamental human rights. One example are the countless forms where you have to emphasise the negative in order to secure the support that’s needed: ‘masterpieces of bureaucratic hurtfulness’ as I once put it. And hardly a day goes by when I’m not asked to give advice to a family struggling to get help. Love is the easy bit, love is the drive but in a society like ours it doesn’t conquer all .

And so what we need, I think, is a new template, a new social contract which recognises the undeniable fact of difference, and does everything in its power to provide help to those who need it most.

And that could allow for a more open-hearted declaration of worth. I recently expressed my condolences to the mother of a learning-disabled young woman who had died of SUDEP (sudden death by epilepsy). Her daughter, I said, was infinitely valuable, as valuable as anyone alive, and had changed the lives of everyone she came into contact with. For the real nightmare is how easily such people are regarded as secondary. As if, as the Nazis would have said, they were leading ‘lives unworthy of life.’

Instead, we should start ‘valuing people’, as the 2001 learning disability report optimistically put it. But that’s 20 years ago and we’re still not there. How long do we have to wait?

+

These many contradictions can be found in disability politics, where virtue signalling, the photo-op, have become all consuming, and too often disconnected from the realities on the ground.

A recent example is the Down Syndrome Act, which sailed through the Commons pretty much uncontested, as if our elected representatives thought that it was an easy win which would make them look good. The Lords did better but couldn’t block it.

Dr Liam Fox’s Private Members’ Bill was championed by a small group of active parents (supported by some fairly unsavoury characters on the anti-abortion right), and the campaign emphasised all the remarkable things that their offspring could do. Ironically, its supporters also insisted that people with Down’s have more severe medical and educational needs than others and require specialist medical and educational provision. Having your cake and eating it, it seems.

The best legal minds have shown just how ineffective this legislation will be in practice. But what really concerns me is that the Act champions one fairly small group (40,000) on the basis of their extra chromosome, and ignores the needs of the other almost 1.5 million learning-disabled people, many of whom require far greater support. I desperately want people with Down’s to have better lives, but the truth is I want everyone with learning disabilities to have better lives.

The essential point is that we should provide support according to need, not by diagnosis, and ensure that we embrace the full range of abilities and impairment and avoid unnecessary division or hierarchy.

The Act is symptomatic of a political culture which is so busy signposting that it ignores the facts on the ground. It fetishizes individual achievement and divides people into categories. It’s opened a Pandora’s box that will be difficult to close.

*

So, what conclusions can be drawn from all these contradictions? Where do they leave us?

Well, the other day a young woman with Down’s Syndrome tweeted proudly that she could cook her own dinner. And, no question, we should celebrate such achievements. But not everyone can do these things — Joey certainly can’t. Pointing this out is not a betrayal of the cause, not a counsel of despair, it doesn’t prove that I’m a ‘pedlar of doom’ (as one of the Down Syndrome Act champions called me). Rather, it’s an insistence that we accept people for what they are and not insist they be something different.

For we are at the moment, I believe, in danger of turning our backs on the people who need help the most, and to whom we owe the most profound duty of care.

And that should worry us.

I think we need to develop a more honest discourse around learning disabilities. A more human one, in fact. One which acknowledges the reality of fragility and weakness, even as it celebrates achievements and independence. One which embraces all our children — the disabled alongside the non-disabled, the clever alongside the less clever — and remembers the dementia that so many of us will face in old age — as I see in Joey’s 90-year-old grandfather, my lovely dad.

All of which is perhaps what my friend the remarkable Welsh vicar John Gillibrand means by ‘the theological model of disability’: a way of thinking about learning disability which is unjudgmental, non-challenging, not interested in categorising, open to individuality and difference, and, above all, the unique value of every human being. And I say that as an atheist.

This, I think, could have two consequences:

The first is that by engaging with the individual realities, support can be useful, empowering and humane. We can help people, not by trying to change them, not by telling them to be better, not by imposing on them meaningless aspirations, not by expecting them to achieve things, but by accepting them as they are, in all their particularities. For learning-disabled people are our brothers and sisters, our sons and daughters, our mothers and fathers. They are us and we are them. It’s time we stood alongside them, and gave them the help that they need.

And that could help the rest of us too.

How?

Well, I sometimes think that looking at the world through the lens of learning disabilities is a bit like the Brechtian ‘alienation effect’. Don’t worry, but this is an approach to aesthetics in which the familiar is exposed as strange, and the odd starts to look entirely natural. And so, by engaging with the realities of severe learning disabilities we can question our own devotion to productivity, rethink what we mean by the meritocracy and, above all, reassert fundamental human value.

And so maybe, just maybe, people with learning disabilities can teach us how to live better lives. We certainly need help from somewhere.

It’s time to be more honest. It’s time to be better.

+

I’d like to end with a passage from Maureen Oswin’s extraordinarily powerful The Empty Hours, a 1971 study of disabled children living in institutions, where she has a heartbreaking conversation with the five-year-old Jason.

Strictly speaking, Jason isn’t learning disabled, but little says more about the situation faced by so many learning-disabled people today. It’s a plea for a better world.

‘Cerebral palsy had given Jason permanently withered limbs and slurred speech’, Oswin writes.‘Family rejection had given him a never-eased homesickness. Social provision gave him a hospital to live in. A lively mind gave him an insatiable curiosity.’

‘Why can’t I purr like a kitten? He asked.

This was fairly easy to answer.

‘Why did my mummy eat me?’

‘Eat you?’ This was startling.

‘Yes, you told me yesterday I was in her tummy when I was a baby. How did I get there, did she eat me?’ After a while this was sorted out to our mutual satisfaction.

‘Where do I keep my tears when I am not using them?’

This was a little harder. He may well wonder where they came from, for he had known more tears than most of us.

‘Why do I get sad such a lot of times?’

All the pat answers from past experience with inquisitive infant children could not rescue me very comfortably from this question.

‘Have I got to stay all my life in this hospital?’

What answer now? I thought of all the brave reforms through social history, the early crude attempts to help the destitute and improve Workhouses, houses and factories. There were all the Committees, Members of Parliament, journalists, civil servants, the charities, the wealthy and the poor, whose opinions and ideals have shaped English social history over the last 200 years. There were Children’s Acts, Housing Acts, Education Acts, Mental Health Acts, the National Health Service, and Acts for Divorce, Criminal Justice and Abortion; there were laws to protect women, homosexuals, animals, immigrants, house purchasers, landlords, street vendors and car-drivers; the twentieth century—the age of human reasoning and compassion. But where did young Jason and his kind fit into this good age of reform and broad thinking?

‘You’re not answering me. Will I have to stay all my life in this hospital? Answer me...’

We still have no proper answers for Jason. Despite everything, learning-disabled people still come last.

We have to do better.

Thank you.

So terrible being the dad of a learning disabled young man. pic.twitter.com/innKcdKFje

— Stephen Unwin (@RoseUnwin) January 1, 2021 " target="_blank" class="sqs-svg-icon--wrapper twitter-unauth">